The pace of technological advances has been astonishing. It took just 66 years to go from the Wright brothers’ first flight to Neil Armstrong having a stroll on the moon. There was less than 40 years between the first computer mouse and the release of the iPhone.

From the excitement of the Channel 5 launch in 1997 bringing the number of terrestrial channels in the UK up to a full handful, we now have access to a seemingly never ending range of streaming services providing entertainment on demand (on a recent rural holiday I struggled to explain to my 5 year old the concept of only having ‘live’ TV to watch…).

One of the latest technological trends is the Internet of Things (IoT for short) – the surge in so called ‘smart’ products that are connected to the internet. Your local electronics store will no doubt be full of appliances that boast of integration with Alexa/Siri/Google (although quite why you’d want to talk to your washing machine isn’t immediately clear…). The dazzling array of smart lights, cameras, doorbells, thermostats etc enable you to monitor your home from the other side of the world, and set up automations worthy of Tony Stark.

While the ‘benefits’ of some of these enhancements aren’t always immediately clear, one area that could be beneficial when it comes to life expectancy is ‘wearable tech’. I explore below some of the potential benefits.

One step at a time

The benefits of regular exercise have long been known. One metric to keep an eye on is simple step count. While the fabled 10,000 step daily goal is actually somewhat arbitrary, it does at least give a target to aim for. A whole range of step trackers are now available, many of which offer some form of gamification to help encourage users to meet their exercise goals.

As technology has advanced, the range of possible measurements has also increased.

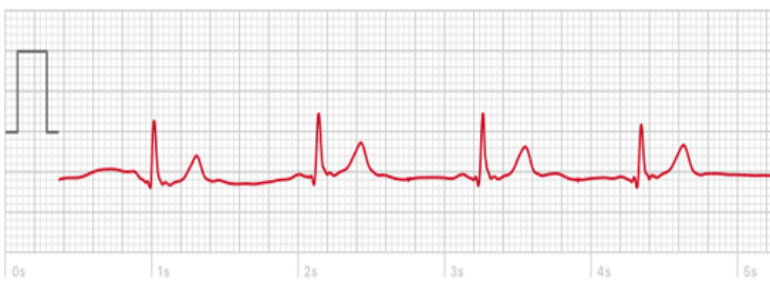

The latest smart watches from the likes of Apple and FitBit can now measure things like heart rate, blood oxygen, sleep patterns and even stress. Built in ECG apps enable users to look for signs of atrial fibrillation (my latest reading looks OK thankfully). My Apple Watch reminds me to wash my hands for at least 20 seconds, to take a moment to breathe, and to regularly stand up throughout the day, and warns me if sound levels are too high. It can also be set to trigger a call to emergency services if it detects a fall.

My ECG reading while writing this blog

There are already numerous stories of smart tech saving peoples’ lives, through highlighting an otherwise unknown medical condition, or helping in an emergency situation.

Another benefit of this stream of health-related data being constantly recorded is that it can help medical professionals with diagnosis. If patients can share detailed ECG readings or heart rates measurements then it enables objective analysis, compared with the much more subjective details typically given verbally. Having a rich history of previous readings can be very useful in determining the ‘normal’ level for the individual, so highlighting where things may have changed. A number of health institutions are now integrating their electronic heath records to enable their patients to get easy access to their own health data – another big step forward.

Widening the pool

While this is clearly of benefit to individuals, there is also potentially much wider health benefits through the use of such smart tech in medical research. Over recent years a wide range of studies have made use of data gathered by smart devices such as Fitbits across a range of fields, including physical activity, chronic pain, sleep patterns and mental health .

One of the typical struggles of any health studies is gathering enough participants, and subsequently gathering and analysing their data – a time consuming and often expensive process. By making use of the proliferation of smart devices this process can be simplified to a few clicks and opened to a much wider potential group. As an example, Stanford University partnered with Apple in a study of how accurate the Apple Watch was in detecting atrial fibrillation. While the results (an impressive 84% match to a full ECG) were impressive enough, perhaps more interestingly the researchers had almost 420,000 participants sign up for the trials. Fitbit have recently launched a similar heart study, looking for up to 250,000 owners to sign up.

Could this be a sign of things to come in the medical research field? Apple certainly think so – they’ve launched the Apple Research app in the US to make the process even easier – the app allows users to easily enrol in a range of health studies, currently including heart health, women’s health and hearing. As companies continue to add more and more measurements to devices (e.g. blood pressure, blood glucose and even blood alcohol) the scope for future health studies is enormous.

Quality Control

While more data is usually preferable to less, there’s always a need to ensure quality too. So while some of the numbers above look impressive, it’s worth remembering that there will still be some issues for researchers to consider. For example, are the ‘right’ type of individuals signing up to your trial? The type of individuals who have the necessary tech, and are aware of and willing to participate, may be limited. If you’re carrying out say a study of the impacts of dementia, participants aged under 50 say are unlikely to be of much use, given the very low prevalence at younger age groups. There may also be thorny issues around old chestnuts like who owns the data and what they can do with it. And recently there’s been reported issues around consistency of reported data – with a change in algorithm seemingly resulting in different data being reported for the same time period when extracted at different points in time.

It seems that smart tech, and wearables, are here to stay, and with ever expanding sensory abilities there’s lots of potential for great health benefits, both for individuals and, through a rapidly expanded pool of potential participants in health studies, wider society.